Ι The Ephemeral Pools Project Ι The Lizards Project Ι The Semi-aquatic Turtles Project Ι The Snakes Project Ι The Stream Amphibians Project Ι

In Awe of Nature: Treasuring Terrestrial Turtles

Reviewers: Amy Germuth, Douglas Lawton, and Lynn Sametz Before starting a project similar to the one described in this curriculum, contact your state wildlife resources commission or state division of fish and game to see what permits you need to work with animals. The following curriculum was developed by The HERP Project to engage participants with the joy and wonder of nature and science through the study of box turtles. The curriculum was developed over several years of working with high school students in our Herpetological Research Experience (HRE) residential program. Feel free to modify this curriculum to fit your educational program. Written by:

Written by:Ann Berry Somers, Catherine Matthews, and Lacey Huffling

This curriculum was developed by The HERP (Herpetology Education in Rural Places and Spaces) Project to introduce participants to the wonders of nature and science through the study of box turtles (Terrapene spp.). The curriculum was developed over several years of working with high school students in our Herpetological Research Experience (HRE) residential program. Feel free to modify this curriculum as needed.

In our program, participants are introduced to turtle biology as well as to The Box Turtle Connection (BTC), our long-term mark/recapture box turtle study in North Carolina. The BTC is designed to follow temporal trends in population size and structure (sex, age class) as well as the health and condition of individual box turtles from numerous sites across North Carolina. The data collected are important to help scientists determine if box turtles need special conservation measures to maintain their populations and thrive in their natural habitat. Our box turtle studies are enhanced by use of Boykin Spaniel dogs to locate and retrieve box turtles and use of radio tracking to determine activity ranges for male and female box turtles. For more information about the box turtle curriculum of The HERP Project, see the UNC TV episode focusing on box turtles.

Special Nomenclature Note for this Curriculum: The Committee On Standard English and Scientific Names (2012) established a standard for names for reptiles and amphibians, which was published by the Society for The Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Included in that document were directives for box turtle nomenclature and standards for capitalization. It was determined that the English name of a subspecies should not be identical to the English name of the species. Previously, the name Eastern Box Turtle referred to both Terrapene carolina and Terrapene carolina carolina. Now, the English name for T. c. carolina is Woodland Box Turtle to avoid conflating the two taxa. The following are the designated scientific names for Terrapene (box turtles) in North America:

- baurii Taylor, 1894)—Florida Box Turtle

- carolina (Linnaeus, 1758)—Eastern Box Turtle

- c. carolina (Linnaeus, 1758)—Woodland Box Turtle

- c. triunguis (Agassiz, 1857)—Three-toed Box Turtle

- ornata (Agassiz, 1857)—Ornate Box Turtle

- o. luteola (Smith and Ramsey, 1952)—Desert Box Turtle

- o. ornata (Agassiz, 1857)—Plains Box Turtle

Woodland Box Turtles and Three-toed Box Turtles are also Eastern Box Turtles, which is the more inclusive category. Likewise, Desert Box Turtles and Plains Box Turtles fall under the more inclusive category of Ornate Box Turtles. Changes in terminology are slow to catch on, and the new term Woodland Box Turtle is not commonly used at the this time. Most people still call them Eastern Box Turtles. To avoid confusion, scientists will sometimes skip the Terrapene designation and use the specific epithet or sub-specific epithet such as “carolina carolina”, “triunguis”, “baurii”, “luteola”, etc. when speaking to another scientist. When discussing specific categories of turtles such as Eastern Box Turtles or Desert Box Turtles, we will use the convention of capitalizing each single word in the name. When discussing box turtles as a group, we will begin each word with a lower case letter so that it will appear as “box turtle” rather than “Box Turtle.”

Central to our program’s success is the inquiry method of teaching and learning. Our programs include discussions, rather than presentations where participants are expected to sit quietly and listen. A successful discussion has participants asking and answering questions. Don’t worry about wrong answers; there will be time to correct misconceptions. Questions like the following are helpful in engaging the participants meaningfully: “What makes a box turtle special?”, “What makes a box turtle a box turtle?”, “How would you describe a box turtle to someone who has never seen one?”, “Can a turtle crawl out of its shell?”, or “What are the names of the scutes (scales) on a turtle’s shell?”

Discussion about box turtle shell video: https://vimeo.com/112868050

After completing this project, participants will be able to:

- Engage in inquiry investigations that demonstrate an understanding of the nature of science

- Demonstrate techniques to safely catch, handle, house (if necessary) and release box turtles

- Demonstrate appropriate use of equipment and measurement tools

- Explain the trapping methods that are used in this project

- Describe human threats to box turtles and some of the actions a person can take to diminish those threats

- List characteristics of box turtles (and other reptiles)

- Distinguish box turtles from semi-aquatic turtles

- Describe the general natural history of Eastern Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina) such as age to maturity, food preferences, home ranges, predators, sex determination, etc.

- Measure and mark box turtles according to the protocol established in The Box Turtle Connection: Building a Legacy (Somers et al., 2017) and enter data in a citizen science database

Leaders of this project do not need a lot of experience, but it is strongly suggested that potential leaders read this curriculum thoroughly as well as other material on box turtles, such as Ken Dodd’s Natural History of Box Turtles (2001). Leaders should also download the free book The Box Turtle Connection (Somers et al., 2017). The book was written to support a long-term citizen science box turtle project and the vast majority of the material in it will be highly useful and should be considered required reading for the instructor. Included are range maps, measuring diagrams, codes for marking turtles, gardening for box turtles tips, how to build a brush pile, and much more. Instructors and other educators may access many educational resources available on the Box Turtle Connection’s website (https://boxturtle.uncg.edu/). Below is background material on box turtles that will be helpful to experienced as well as novice instructors, but is not a substitute for the materials mentioned above.

A Brief Primer on Box Turtles

Box turtles are a group of closely related turtles found in central and eastern North America, and many regions of Mexico. Many people find box turtles engaging and charismatic, and, because of this, they are particularly good subjects for connecting students to nature and interesting them in science. Furthermore, box turtles are an essential part of the environment and are the state reptile in four U.S. states (North Carolina and Tennessee [Eastern Box Turtle], Kansas [Ornate Box Turtle], and Missouri [3-Toed Box Turtle]). All but one of the box turtle species are terrestrial. They are omnivores, contributing to the food web both as predators and as prey. They eat a variety of plants, mushrooms, and insects and dine on carrion when the opportunity arises. Box turtles are also some of the slowest reproducing species in the world. Females do not reach sexual maturity until around the age of ten. Compare this with a white-tailed deer who can birth a fawn at 18 months of age. In the 10-12 years it takes a box turtle to lay her first clutch of eggs, there could be seven generations of deer.

Scientists suspect that box turtle populations are declining due to habitat fragmentation and destruction, disease, and mortality from lawn mowers, tractors, bulldozers, and car strikes on roads. Many young turtles and some adult turtles fall prey to raccoons, coyotes, turkeys, and domestic dogs. Since most box turtles have small home ranges, building roads for housing developments and shopping malls may mean cutting through their home places. Often, turtles must cross roads to reach food, water, mates, and safe places to overwinter which puts them at risk of being hit by cars or moved to unfamiliar territory by well-meaning people. A box turtle moved from its home may spend the rest of its life trying to return home. By studying box turtles, we can learn more about the turtle’s migration patterns, reproduction, health, and habitat choice. We can also learn about the human-caused threats to long term health of populations. Like people, some box turtles can live to be more than 100 years old.

Scientists know that box turtles not only can live a long time, they must live a long time. Because box turtles have low reproductive rates (few eggs and hatchlings each year, with high mortality in these life stages), they must live a long time in order to leave at least two offspring that will survive to adulthood, one to replace both mates. When this occurs, population sizes remain stable. But scientists believe that populations of box turtles in many places are declining (Swarth and Haygood, 2004). In North Carolina, they are considered a species of “greatest conservation need” and are listed as such in the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s NC Wildlife Action Plan. The North American Box Turtle Conservation Committee holds meetings biannually in different parts of the range of Terrapene (box turtles) to provide a forum for the latest scientific research and to promote networking among the conservation-minded.

|

|

Although some people think turtles can survive any injury, this is far from the truth. Some box turtles have shell injuries (nicks, scratches, missing pieces) or missing limbs (a back foot, a partial leg), but these are the ones that have been able to survive the mishaps that caused these deformations. Although turtles are hardy creatures in general, there is no such thing as a superturtle. They can and do die from injuries and disease. Box turtles catch colds and get fungal, bacterial, and viral infections. One particularly bad virus is the ranavirus, which causes respiratory distress and has been responsible for mass die-offs of box turtle populations in the wild and in captivity. If a box turtle is found with a gaping mouth and the inside of the mouth is covered with white or yellow pasty lumps, then a wildlife veterinarian should be contacted immediately and the animal should not be released back into the wild. Ranavirus is very contagious to other turtles and amphibians, and it is important to isolate a sick turtle. This is yet another reason why transporting box turtles to new locations is dangerous, as these turtles could be vectors of disease that could spread quickly within the turtle population at the release site.

Why study box turtles? video: https://vimeo.com/112868941

- Shells of dead box turtles and various semi-aquatic turtles (many state museums and nature centers have loaner collections)

- Calipers (6” long or greater, preferably with jaws of 2.5” or longer)

- Digital scale or spring scale

- Triangular file

- Data sheets (Appendix A, C)

- Diagram of turtle shell with marginal scutes coded

- Turtle Identification Codes (Appendix E)

- GPS (available on smartphones)

While doing fieldwork in North Carolina, participants may encounter chiggers, yellow jackets, ticks, and spiders. Using insect repellant (but not on hands if participants plan to handle herps) and wearing a hat and long pants are useful ways of preventing these animals from biting, stinging, or attaching. Clothes can be pre-treated with insect repellant (such as Permethrin) instead of applying insect repellant to the skin. Pulling crew socks over the bottoms of pants legs is an especially good way of preventing ticks, chiggers, and spiders from crawling up legs.

Participants should also engage in safe fieldwork practices. They should wear sunscreen and carry drinking water. In hot weather, make sure participants are well hydrated; ask them to stop and drink water at regular intervals to help prevent heat stroke or other complications. Sturdy boots are useful when hiking in rough or overgrown terrain. If an area may contain snakes, know that feet and ankles are the most common bite locations, followed by hands. Wear protective footwear (such as rubber work boots to cover calves), long pants, gloves (such as leather gloves), and look before placing hands down or around a tree. Always hike with a partner and let someone else know the itinerary.

Handling live animals can be exciting but precautions should be taken to ensure the safety of the animals as well as the participants. Always wash hands before, after, and between handling animals. Never taunt an animal or put fingers near its mouth.

Although turtles do not have teeth, they have a strong, powerful mouth that acts like a beak. Any turtle can bite and scratch you with their nails although eastern box turtles rarely bite. Be prepared though to be bitten or scratched. Keep the turtle’s head aimed away from you so it can’t latch on to a nearby part of your body. Never place your hands in front of the turtle’s face or even close to its head. Some turtles have very long necks and can reach around to bite. Pick turtles up by holding the whole shell between both hands slightly in front of the hind limbs, keeping fingers away from the mouth area. Grip the carapace (top shell) on both sides above the hind legs (thumbs on the carapace and fingers on the plastron). Always be mindful of turtles with long necks! Handling turtles can be tricky. When handling turtles they often try to “swim” in the air. Being handled by humans is a terrifying experience for the turtles, best we can tell. Respect the natural inclinations of these ancient creatures, and leave them near ground level. Dropping turtles from even a few feet may harm them.

Start a session by passing around different turtle shells (box turtles, semi-aquatic turtles, and marine turtles) so participants can examine them prior to discussion. When questions are presented, everyone should listen to the responses without interrupting. Writing responses on a white board is helpful. The following questions can be asked, but be sure not to provide answers until many participants have been able to answer. When possible, use participants’ answers or parts of their answers to clarify our current scientific understanding of this information.

The thin plates covering the bony shell are called scutes and readily fall off after the turtle dies.

What is a turtle shell? Modified ribs and vertebrae that serve as protection against predators. Turtles are the only vertebrates with shoulders and hips inside their rib cage, which is their shell. The plates on the bony part of the shell are modified scales called scutes.

- What does the word “marginal” mean? Which of the scutes do you think would be called the marginal scutes? Marginals are the scutes around the edge of the carapace.

- What about the vertebral scutes? Vertebral scutes are down the middle of the back shell, down the backbone.

- What are the parts of a turtle shell called? The top shell is the carapace and the bottom shell is the plastron. The link between the two shells (carapace and plastron) is called the bridge. The hinge is the part of the plastron that connects the front part (anterior) with the back part (posterior) and allows the plastron parts to move independently.

- Where do box turtles live? They are found in a variety of habitats from forests to wooded swamps to dry, grassy fields. The coloration on their shells provides great camouflage in all of their habitats. Box turtles need different types of areas to thrive and will move among them throughout the year as food or other resources become available. For example, they will be found near fruiting plants, such as blackberry bushes, when they are bearing fruit and will move to wet areas during dry weather. Certain types of palatable mushrooms may only grow in one part of the forest at certain times of the year, making this area of the forest temporarily attractive for the turtles. Box turtles need moisture during overwintering and hot mid-summer spells, so they may frequently travel to areas with hydric (wet) soils, streams, ponds, ditches, or springs.

- What do box turtles eat? A variety of foods, including worms, slugs, berries, mushrooms, and garden tomatoes.

A hatchling box turtle. The bridge connects the carapace (top shell) and the plastron (bottom shell) and is located between the front and back legs.

|

Watch Eastern Box Turtles eat video: http://vimeo.com/112705741

Participants can now be asked to sort the shells based on their shapes and discuss the relative merits of each shape for terrestrial life or aquatic life. While looking at the shells, participants can be asked, “What makes a box turtle’s shell special?” The shape of the shell is generally oval and the turtle can shut itself completely inside to protect itself from predators. The central hinge allows the shell to completely close and the box turtles can pull its head, legs, and tail fully into the shell. Ask participants to create a dichotomous key using either real shells or, shell models made of clay or model magic. Painted turtle and snapping turtle shells can be purchased online.

Mark-Recapture

|

In a mark/recapture study, it is possible to tell if a turtle has been caught before because each turtle has been marked with an individual code (three notches representing three letters). Each turtle is marked on its shell by filing a “V” marking on three marginal scutes (scutes around the margins of the top shell). The carapace of a turtle usually has 24 scutes around the perimeter and each scute represents a letter in the alphabet, A to X. Marking each turtle by filing three notches with a triangular file will allow participants to identify the turtle if it is recaptured or determine if the turtle has moved location, gained weight, or been injured. For a complete explanation of the marking system and a list of the codes, refer to The Box Turtle Connection: Building A Legacy (Somers et al. 2017).

Data Collection

Data collection includes various measurements of the turtle’s body, descriptions of habitat, environmental conditions, and location (use GPS to determine the coordinates). Box turtles are then sexed, measured, and marked. The best way to determine the sex of a box turtle is by looking at a turtle’s plastron, tail length, and eye color, though there are many other sex characteristics, including shape of the shell and the curvature of hind foot toenails. Males often have longer, wider tails than females, a plastron that has an indentation, and red eyes. Females have thinner tails, a flat plastron, and usually have brown eyes. “Sexing Box Turtles” has more information about sexing turtles and includes a quiz.

At one time, it was thought that the age of a turtle could be determined by counting its annuli, which are the rings on each scute of a turtle’s carapace or plastron. A number of studies have challenged this assumption (e.g. Litzgus and Brooks; 1998; Moll and Ledger 1971; Wilson et al. 2003). We agree with Wilson et al. (2003) that aging turtles using annuli should be viewed with skepticism. The only way to know the age of a turtle is to be there when it is born. Annuli may better represent a growth period rather than a year of life. Growth in turtles can be interrupted for overwintering but also for periods of reproduction in females, drought, illness, periods of excessive rainfall, and other unknown causes.

Box turtles are weighed with either a spring scale, clipped onto the back end of the shell’s scutes, or by placing the box turtle on a digital scale. If using a spring scale, have a partner put their hands under the turtle for support in case the clip releases. Record the weight when all hands are off the turtle and the turtle is hanging from the scale. Platform digital scales are safer.

Box turtle shell measurements are taken with calipers. The carapace length and width, the plastron length from hinge to anterior end and hinge to posterior end, and the total plastron length are all recorded. The height of the turtle (from carapace to plastron) is also measured. Refer to the diagrams in The Box Turtle Connection, which include detailed illustrations of the measurements. Release all box turtles at the point of capture as soon as data have been collected and, in a mark-recapture study once the turtle has been marked.

Measuring the minimum straight carapace length (SCL) of an Eastern Box Turtle using long-jawed calipers.

Locating and Capturing Box Turtles

Superbly camouflaged, box turtles are very hard to find. Many of our turtles are found accidentally as we move about our sites, walk trails, or drive. Deliberately driving roads in search of reptiles and amphibians is called “road cruising” and, at times, this can be a very successful method of locating turtles. Late spring and summer rains stimulate movement, so the chances of finding them on these days is increased. Another method is to conduct a census with a group of 4-12 people in a defined area (like one hectare), anytime between the hours of 10 am and 4 pm. The protocol is described in “How to Conduct a Box Turtle Census,” a chapter in The Box Turtle Connection.

Occasionally, we use highly trained turtle-dogs (Boykin Spaniels) to help us locate box turtles at our study sites. John Rucker, a naturalist, outdoorsman, and a former middle school teacher, has trained his Boykin Spaniel dogs to find and gently retrieve box turtles on command. Animal Planet produced a video about the breed featuring John’s dogs. John and his dogs have made important contributions to research across the ranges of the various species of Box Turtles.

Radio Tracking Box Turtles

We attach transmitters to turtles so that we can easily locate them and track their movements. Radio tracking is an excellent method for learning about turtles and, with practice, it becomes easier, though at first it can be frustrating. For a detailed explanation and practice exercises, read Brian Cresswell’s “Practical Radio-Tracking.” Our radio tracking data sheet can be found in Appendix C.

A transmitter, glued onto the shell of a turtle using a standard five-minute epoxy, emits a signal via radio waves at a frequency that is picked up by a receiver carried by the participant. The attached antenna widens the area of reception and, when the signal is detected, the receiver beeps. The beeps get louder and more frequent the closer the receiver is to the transmitter. Some receivers also have a visual signal, like a needle on a scale, and the needle moves to higher numbers as the receiver gets closer to the transmitter.

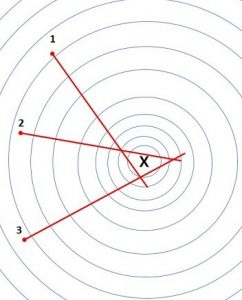

Testing for the radio signal from several different locations allows the observer to move accurately towards the approximate location of the telemetered animal. In this illustration, the testing points are 1, 2, and 3 and the location of the turtle is indicated by the X located in the triangle produced by intersecting lines.

Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates should be recorded at each box turtle location. Tracking several times a week is a good idea; start where the turtle was last located. Although box turtles have fairly small home ranges and do not typically move very far in a day, they occasionally strike out and move greater distances to look for food, mates, or a place to lay eggs. Becoming proficient at using telemetry equipment takes time and practice, so we typically do this in small groups or pairs.The approximate location of the turtle can be determined by using a technique called triangulation, which is determining the location of the transmitter from several points, extending those points into lines of and deciding where those lines intersect. Begin by rotating slowly in a circle finding the strongest signal. Walk towards the signal stopping several times to reassess signal strength and direction. Then, deliberately walk past or at an angle to the strongest signal reading; repeat the same action to get several linear measurements that help pinpoint more specifically the location of the turtle. The technique of walking towards the signal and passing it avoids the problem of stopping too soon to do a detailed search in a small area when the turtle is actually many meters away. Once the receiver is very close to the turtle, examine the ground closely and point the antenna to the ground until the box turtle is found. If the antenna is detached from the receiver, the receiver can be skimmed along the ground to find a box turtle that is nestled under leaves or mud.

Always release turtles where they were found. Well-meaning people harm turtles without realizing it, believing they are doing a good deed. They sometimes move box turtles that are crossing roads to new, distant locations. However, box turtles are home bodies and do not adjust well to unfamiliar habitats. To help box turtles that are crossing the road, safely move them to the side of the road they are headed toward. To raise awareness, print out the Box Turtle post card (Appendix D), on our website (theherpproject.uncg.edu) and place them in obvious places (like on refrigerators) to serve as a reminder of why turtles need to stay in their own wild homes.

Data Reporting to The HERP Project and HerpMapper

Participants may use the free Herp Project app (available for download at http://theherpproject.uncg.edu/apps-collecting-data/) to record data and upload it to an open-source database found on the Herp Project website (http://nc-herps.appspot.com/), which is available to everyone. This enables comparisons of current data with those collected in previous years and previous sites. Another citizen scientist website for uploading data is Herpmapper (https://www.herpmapper.org/).

Scientists interested in accessing the long term mark-recapture data collected as part of the Box Turtle Connection project should send a request to the authors of this curriculum with information about how the data will be used. This database contains records of thousands of box turtles collected since 2008 at over 30 sites in North Carolina.

Websites

Davidson College Herpetology Eastern Box Turtle http://bio.davidson.edu/herpcons/herps_of_NC/turtles/Tercar/tercar.html

The Box Turtle Connection website: http://boxturtle.uncg.edu/

Books and articles

Beane, J. C., Braswell, A. L., Mitchell, J. C., Palmer, W. M., & Harrison, J. R. (2010). Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Committee on Standard English and Scientific Names. (2012). Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North American north of Mexico, with comments regarding confidence of our understanding. Herpetological Circular no. 39. Salt Lake City, UT: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). (2007) Student Standards

https://www.iste.org/docs/pdfs/20-14_ISTE_Standards-S_PDF.pdf

Litzgus, J. D., and R. J. Brooks. 1998. Testing the validity of counts of plastral scute rings in spotted turtles, Clemmys guttata. Copeia 1998:222–225.

Moll, E. O., and J. M. Legler. 1971. The life history of a neotropical slider turtle, Pseudemys scripta (Schoepff), in Panama. Bulletin of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Science 11.

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Somers, A.B., C.E. Matthews, and A. LaVere. 2017. The Box Turtle Connection: Building a Legacy. Online at http://boxturtle.uncg.edu/BTC-Building-a-Legacy.pdf.

Swarth, C., and S. Hagood. 2004. Introduction. P. 32 in Swarth, C. and S. Hagood (eds.), Summary of the Eastern Box Turtle Regional Conservation Workshop. The Humane Society of the United States.

Wilson, D.S., C.R. Tracy, and R. Tracy. 2003. Estimating age of turtles from growth rings: a critical evaluation of the technique. Herpetologica 59(2): 178-194.

Visual learning software

VL HERPS is a free visual learning software program designed for learning reptiles and amphibians of the Southeast at home. http://theherpproject.uncg.edu/visual-learning-software/

This project is supported by the National Science Foundation, Grant No. DRL-1114558. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Transcript of What do box turtles eat?

Christine: They’re really interesting in the way they hunt and so I want you to see, yep, let’s get not focused on her but on, there you go, see? I want you to watch how they hunt and how they eat.

(box turtle snaps at worm) Do you see where he went for first? He went right for the head. He didn’t do a good job of catching it but he went for it.

(Talking to the female turtle) I’ve got one for you too, here you go.

So, and the cool thing is, see how they’re very visual? Different animals hunt different ways: some use hearing, some use smell. You can see that they’re visual hunters, you can see how they kinda look at it. They look at it and then they kinda figure out where they’re gonna bite it and then they come down on it.

Participant: Do they always make that noise?

Christine: When they eat slimy things they make that noise. When turtles eat… The other thing they really like to eat is slugs and a turtle eating a slug is just hilarious because, you know, slimy slugs are….

(Talking to the female turtle) You ready?

I’ll put this one further away so you can watch her see it.

(Female turtle walks up to worm and bites it) So you see, she’s gone right for the head. You see she watches, she sees where it is, she’s looking at it, and then they go right down. I think that’s really interesting, I really enjoy watching the turtles. So, I think it’s pretty cool.

So, they’re omnivores, which means what?

Participant: They eat plants and animals.

Christine: Right. Since they eat earthworms, and they eat slugs, what else or what other meat do you think they might eat in the wild?

Participants: Insects.

Christine: Right, well, think about it, what kinds of insects would they eat? Where are they going to be located, where are these guys located?

Participant: Snails.

Christine: Like, you know, they grubs, and I learned yesterday they also eat millipedes. I didn’t think anything could eat millipedes because millipedes have a toxin.

I know, do you see her looking at me? (Talking to the female turtle) Would you like a strawberry next? I don’t know if she’ll want a strawberry.

(Christine drops a worm and a strawberry in front of a turtle) Look, look, look, here you go.

So, they’re going to finding the type of animals, the type of organisms that live under logs, right? So, beyond the worms, they also eat plants, right, vegetation. So what types of vegetation do you think they would eat?

Participant: Mushrooms.

Christine: They eat mushrooms. And one of the interesting things that you guys know or you should know, that many of the mushrooms that grow out in the woods are toxic to us, right? They are not to the box turtles and so, um, what the Native Americans found out was that sometimes they would eat box turtles and end up with stomach aches. What they found out from watching was that box turtles ate poisonous mushrooms and then they ate those box turtles, then they got sick. So it’s kinda like the poison dart frogs, it’s kinda the same way, they’re only poisonous if they eat a certain kind of ant that has that toxin. The box turtles are the same way so if they eat a poisonous mushroom and then we were to eat them, then that toxin, it stays in their body for a while so that they would be toxic for a bit.

Participant: How long does the toxin last?

Christine: You know, I don’t know how long the toxin lasts but it may be dependent on the type of mushroom, because some mushrooms are more toxic than others, and how much they ate. I think all those factors would come into play on how long it would stay in their system. So that’s a good question.

So they eat mushrooms and we know they eat strawberries as they’re trying to eat it. What else do you think they eat, that’s plants?

Participant: Blueberry

Christine: They might eat some blueberries. There’s another berry that they really really like that grows wild, kinda, lots of seeds, they’re thorny…

Participant: Blackberries?

Christine: Blackberries! They LOVE blackberries, and actually a lot of baby box turtles will go to the blackberry bushes when the blackberries ripen and just hang out there for a while and eat the blackberries. So if you have blackberries growing in your yard, it’s a great thing to have and don’t get rid of them because they’re important for the baby box turtles.

Any other thoughts on what they might eat other than mushrooms, berries?

Participant: Roadkill?

Christine: Oh yeah, I didn’t know that until recently, I was reading something, but yes, they will eat dead animals. That’s part of their meat thing.

So they’re not picky, it doesn’t seem like they’re very picky eaters. Do they have teeth?

Participant: No.

Christine: Are there any turtles that have teeth? No turtles have teeth. All turtles have beaks. They actually have a sharp, if you were able to see their skull you could see there is a sharp plate that goes around with kindof a point at it, and that is the beak that they use to eat.

Transcript of Why study box turtles

Hayley: So why do you guys think that we are paying specific attention to box turtles? Why are we trying to study them?

Participant: Because they’re endangered?

Hayley: So, that’s a good answer, a lot of people think that, but, they’re actually not endangered yet, but they are of concern because the numbers are declining. So they’re not yet to the point where they’re like a panda which is really, super endangered, but we’re noticing a decline, especially in babies. So when they do studies, they’ll find lots of adult turtles and they for, you know, 100 years. So they’ll find ones that are, you know, full grown, have been living for a while but there’s not as many hatchlings as we would like. So these turtles will eventually get to the point where they’re too old to lay eggs, or they’ll get old and pass away, we want to make sure there are enough babies to replace them. And so we don’t quite know why.

Do you guys have an idea of why we’re losing so many babies or where our box turtles are going? Just any guess, it doesn’t matter.

Participants: The eggs get destroyed.

Hayley: Yeah, so that’s one thing that is a danger to them, like rats, you know, raccoons, lots of our native predators can go after box turtle eggs and hatchlings. So that’s one of the dangers to the babies. And then, for the adults, what do you think happens to the adults?

Participant: They get hit by cars?

Hayley: Yeah, so, when they’re, you know, this big and solid, they really don’t have a whole lot of natural predators, they’re pretty much a fortress. But they do encounter troubles when they’re crossing our roads and they get hit by cars because a lot of the times, you know, they’re just trying to get to a place where they would lay their eggs and, they’re not designed to understand how roads work so they walk the same route they’ve always walked. When there’s a road there one day they get hit by cars. And that’s kinda what happens to a lot of turtles.

The HERP Project:Box Turtles July 2017(docx) OR Box Turtles July 2017(pdf)